Today is the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter, which commemorates the teaching authority of the Church, the Magisterium. One of the decisive issues that drew my husband and I to the Catholic Church was the realization that, as I said in my conversion story,

Today is the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter, which commemorates the teaching authority of the Church, the Magisterium. One of the decisive issues that drew my husband and I to the Catholic Church was the realization that, as I said in my conversion story,... without an outside, institutional authority making the final call, it is impossible to maintain either orthodoxy or unity in the church....

Having experienced first hand what a church in chaos looks like (the Episcopal Church), we are especially grateful for this particular aspect of the Catholic Church. But of course, as we have found so many times since entering the Church, there is much more to it than that. We have learned that giving up our insistence on our own private judgment, far from being a hindrance, has instead made us more keenly aware of the meaning of true freedom in Christ.

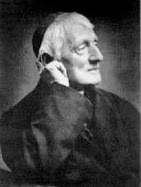

Along these lines, I was struck by today's "Meditation of the Day," in Magnificat, by Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson, an early 20th century Anglican convert. It is entitled The Grace of the Chair of St. Peter:

Turn, then, once more to the Catholic Church and see how in the Life which she offers, as in none other, there is presented to us a means of fulfilling our end. For it is she alone who even demands in the spiritual sphere a complete and entire abnegation of self.

From every other Christian body comes the cry, Save your soul, assert your individuality, follow your conscience, form your opinions; while she, and she alone, demands from her children the sacrifice by hers, and the obedience of their will to her lightest command. For she, and she alone, is conscious of possessing that divinity, in complete submission to which lies the salvation of humanity. For she, as the coherent and organic mystical Body of Christ, calls upon those who look to her to become, not merely her children, but her very members; not to obey her as soldiers obey a leader or citizens a government, but as the hands and eyes and feet obey a brain.

Once, therefore, I understand this, I understand too how it is that by being lost in her I save myself; that I lose only that which hinders my activity, not that which fosters it. For when is my hand not itself? When separated from the body, by paralysis or amputation? Or when, in vital union with the brain, with every fiber alert and every nerve alive, it obeys in every gesture and receives in every sensations a life infinitely vaster and higher than any which it might, temporarily, enjoy in independence?

It is true that its capacity for pain is the greater when it is so united, and that I would cease to suffer if once its separation were accomplished; yet simultaneously, I would lose all that for which God made it and, saving itself, would be lost indeed…In losing my individualism I have won my individuality, for I have found my true place at last. I have lost the whole world? Yes, so far as that world is separate from or antagonistic to God’s will; but I have gained my own soul and attained immortality. For it is not I that live, but Christ that lives in me.